09 November 2015 by Nick Haslam

A Drive along the Alabaster Coast

With history, nature and liqueur on offer, it’s easy to understand why the Alabaster Coast is such an attractive destination, as Nick Haslam explains.

With history, nature and liqueur on offer, it’s easy to understand why the Alabaster Coast is such an attractive destination, as Nick Haslam explains.

Standing high on the coastal footpath above Etretat, my wife and I catch the sudden grey flash of a pair of diving peregrines swooping down through layers of gliding seagulls, sparking indignant waves of alarm calls before they vanish beyond the high arch of chalk cliffs.

“We’re on an avian migration superflyway here,” says Cyrique Lethuillier, an expert on the coast and its birdlife. “I often see those two on the lookout for an unwary bird on its way north to Scandinavia or the UK!”

Trouble for the gulls perhaps, but for us it is the perfect reward for our decision to spend a leisurely couple of days exploring Normandy’s Alabaster Coast.

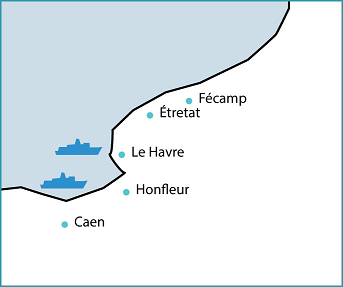

Caen to Honfleur

Landing in Caen barely 24 hours before, on the overnight ferry from Portsmouth, we have a breakfast of croissants and coffee in Honfleur, a picturesque small port tucked beneath hills not far from Le Havre. Exploring the narrow cobbled streets, we stumble across the beautiful wooden church of Sainte Catherine, the largest in France, built by shipwrights in the late 15th century, the high vaulted roof with curving supports like ribs resembling a massive upturned boat.

Outside, a group of artists is busy painting the bell tower, the latest in a long succession of painters drawn to the coast here by the dramatic light.

Outside, a group of artists is busy painting the bell tower, the latest in a long succession of painters drawn to the coast here by the dramatic light.

Both Turner and Corot have painted here, and Eugène Boudin, a friend of Monet whose father had been an Honfleur harbour pilot, was one of the first plein-air painters, setting up his easel on the quay to catch the subtleties of the ever-changing skies.

North to Le Havre

Under suitably Boudinesque high scudding clouds we drive north again that afternoon, crossing the spectacular Pont de Normandie into Le Havre, a city which was devastated by bombing raids during the Second World War.

Largely rebuilt in the 1950s under the direction of the forward-thinking French architect Auguste Perret, the city centre is formed of apartment blocks and squares, built of multi-textured concrete, which the modernist Perret regarded as the new man-made stone.

His most iconic building is St Joseph’s Church, the hollow steeple some 17 storeys tall rising like a needle above the port, its lofty interior lit that afternoon by bright sunlight streaming through a myriad of individual stained glass windows.

We visit the “Witness Apartment” close by, where one of the first flats to be completed in the 1950s is decorated entirely with period furniture and fittings, its parquet floors and large, light rooms with high ceilings easily explaining why residents bombed out of their homes were so happy to move into such modern comfort.

As far as possible, communities were kept together and rehoused in apartment blocks where their homes had once stood. That night we stay in the Perret–designed Hotel Oscar, its original 1950s decor carefully restored, complete with steel balustrades and polished concrete pillars, which are once more very fashionable in current architectural design.

Etretat

Next morning we head along the high chalk cliffs of the Alabaster Coast to Etretat, a tiny fishing village perched on a wide beach of large pebbles. Above the town, on a knoll overlooking the valley, stands the farm of Le Valaine, a pretty manor of the 18th century with a chequered facade made of black and white flint. The owner, Bernard Dherbecourt, produces award-winning cheeses and chocolates made entirely from goats’ milk.

Next morning we head along the high chalk cliffs of the Alabaster Coast to Etretat, a tiny fishing village perched on a wide beach of large pebbles. Above the town, on a knoll overlooking the valley, stands the farm of Le Valaine, a pretty manor of the 18th century with a chequered facade made of black and white flint. The owner, Bernard Dherbecourt, produces award-winning cheeses and chocolates made entirely from goats’ milk.

On a whistle-stop tour of the farm, we meet his docile herd of goats housed in considerable comfort in a 13th century barn close to the manor’s large stone dovecot – I learn to my surprise that this was the first thing destroyed by peasants following the French Revolution in 1789.

“Pigeon eggs were at the time reserved only for aristocrats, and no one was allowed to hunt the birds,” Bernard tells us with a smile. “You can imagine the fury of the peasants here who saw their recently hand-sown fields picked clean by fat blue-blooded pigeons!” Looking down the peaceful valley it is difficult to imagine furious scythe-wielding labourers bent on destruction streaming up to the manor.

In Etretat, the narrow cobbled streets ring with the cries of happy children running down to the wide pebbly beach. In the 19th century the town became very popular with well-to-do Parisians coming to take fashionable sea water cures, and today in the bright summer sun a few tourists are searching in rock pools.

A series of black and white photographs of the 1890s along the promenade give hints of harder times, with fishermen and their entire families laboriously turning huge capstans to pull their boats from the sea. Today one of the old fishing boats has a more prosaic use, and with a tiny thatched roof is used as a summer café and lending library for those who want to read on the beach.

Onwards to Fecamp

We head on that afternoon to Fecamp, once one of the busiest ports on the coast, with many locally built ships sailing for the rich fishing grounds of the Grand Banks off Newfoundland. On the quayside a row of narrow houses of the harbour’s pilots still face out to sea.

That night we stay in considerable luxury at a recently restored chambre d’hote set in a former monastery, where a turret room was used by monks centuries before to spy on returning ships to ensure the church received its dues.

In the morning, as church bells ring, we walk to one of the most extraordinary buildings in Fecamp – the mass of neo-gothic towers and steeples, ornate gargoyles and stained glass windows of the Benedictine Palace.

In the 1850s Alexandre Le Grand, an astute local businessman, said he had discovered a 16th-century recipe by a Benedictine monk for a miraculous health-giving elixir.

With judicious tweaking and additions of highly secret ingredients, the liqueur bearing the same name was launched with great success on to the world market. Le Grand’s son Auguste invested his profits wisely, building this huge edifice to house the new distillery, and in lofty rooms heady with spices imported from all over the world, vast stills produce some three million bottles each year.

Tasting a delicately flavoured sample at the end of our tour we raise our glasses to the massive stained-glass window depicting Alexandre Le Grand seated like an emperor before his Palace, but drink with care. The liqueur is 40 per cent proof, and this afternoon, with some reluctance, we will leave the coast to drive back to Le Havre and our night ferry home.